The Terrorist and the Rhetorician

An Interview with Hadley+Maxwell

Towards is pleased to present a new interview with Berlin based artists Hadley+Maxwell. The interview was conducted by Toronto based “FRIENDS” (Aryen Hoekstra and Jenine Marsh) in fall 2012 as part of the University of Guelph’s visiting artist lecture series.

Aryen Hoekstra: You relocated from Vancouver to Berlin in the fall of 2006. Could you talk about why you chose Berlin and what that location contributes to your practice?

Maxwell: We went there on the Canada Council residency and within 6 months we started to become anxious about the fact that we were going to be leaving. About 6 months in we decided to stay to relieve the anxiety of having to leave and we found that we were having a lot of anxiety about what to do. We had this huge beautiful studio in a building that used to be a monastery. It had 4.5-5m ceilings and was the biggest studio we have ever had and we kept laughing at ourselves because we had 2 desks and a computer in this enormous studio. We had all these studio visits and we’d be showing people things on the computer.

Hadley: A part of that, I think, was that we had worked under a Vancouver paradigm of making and in some ways were rebellious at first. At the time we left we were starting to appreciate a lot of the things about the so called Vancouver school, and the way that it constructed itself around a certain narrative of artistic production. But when we got to Berlin we realized we were free and…

Hadley+Maxwell: We could do anything!

Maxwell: And for us it was a trauma. What do you do when you can do anything? Of course we could always have done anything, but for some reason the community that we were used to, that discursive community wasn’t right there with us, and we felt the weight of the freedom of doing anything. It really caused us to do a lot of soul searching. What it meant to us to be artists and what it meant to commit to being artists and that’s why we stayed; because Berlin represents this context for us where we can do anything and there are so many communities of artists there working in every way you can imagine. If you start to become interested in something there’ll be somebody there to have that conversation with. And we were beginning to feel that Vancouver was limited in those opportunities. Our work changed dramatically and continues to change and we feel like that’s a really good reason to be somewhere.

Jenine Marsh: Having heard you speak in the past, you’ve posed the question “Who does the work produce?” How do you see your role in your works in relation to that of maker, viewer and participant? Is that a fluctuating role, or do you aim in a certain direction? Do you allow for change within your role?

Hadley: It’s multiple in a way. We grew up through art school and have been in art school continuously and there is this paradigm that’s really more centered around the human sciences in a way, moving away from studio mentorship. We learned critical models almost before we learned technical skills, which has its good things. We have strong critical skills, but we’ve also realized that’s paralyzing. It’s hard to simply make things and this is the paradox of it: We’ve come to this conclusion through critical thinking, that we need to kill critical thinking to a degree. Part of our solution to that is to change our relationship to making and audience.

<radiator turns on>

Maxwell: That’s a great interruption. In a way that buzzing is letting the world in, in ways that you’re not controlling and you have to find a way to respond to that. This rhetoric around the audience almost was an overwhelming noise, and we had to find a different way of turning that down. Fortunately as a collaboration we have each other to perform that role, so one of us can kind of be immersed in it, through processes like answering this question and the other one can be reflecting. Within a pair or collaboration you have both maker and audience in the same corpus so to speak.

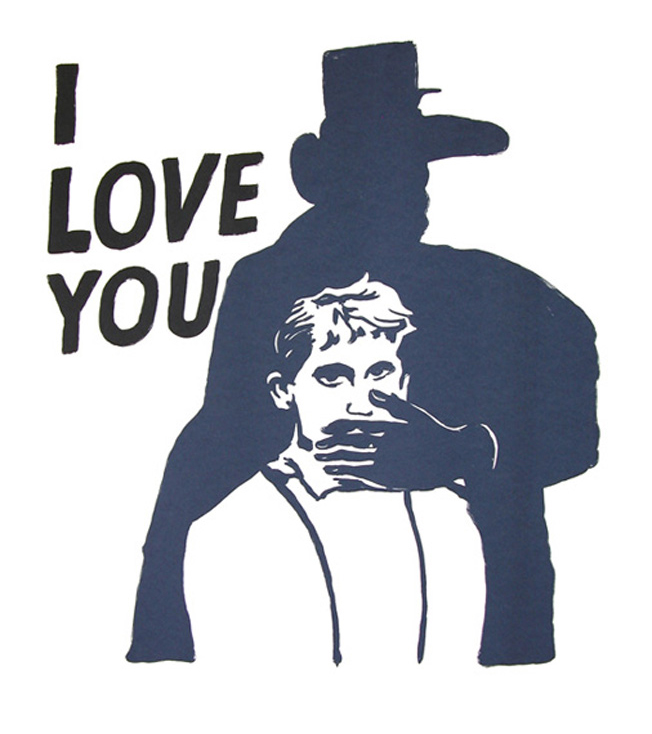

Hadley: Well that’s what we realized quite early on, with the help of philosophy, and Agamben in particular. We understood that within the institutional format that we emerged from every artist is ultimately split between the rhetorician and the terrorist, or the person who’s alone in the studio and the person who has to open the studio door, or the critic and the maker. We’ve always been interested in that split and watching that occur and trying to figure out how to be more on the side of the maker, but as Max was saying, working together is a way of externalizing the splitting. That happens in every artist that we talk to. I think that it also is a traumatic split. One that we are all dealing with. We’re expected to be able to articulate all of our decisions and that means that you’re constantly translating things into linguistic terms, and we don’t really let it rest in other forms of language.

Maxwell: Further to that, we find ourselves in a position of trying to control less this split between your desire to make something and your inability to act until you’ve conceived of what it is your going to make. It’s this passage that we are trying to kill. We realized that in the aesthetic conception of an artist, there’s a person before there’s a work and then there’s the work. Instead we aim to make it a kind of continual relation of making. This means that sometimes you’re a witness to your own process; you’re a witness to your own impulses; you’re a witness to your own intuition, like an audience would be. You just hope that the audience will share something of that.

Aryen Hoekstra: You spoke about the role of the viewer in your installation 1+1-1 (2007) as that of the editor, as being involved in the act of splicing together a montage. Do you see the term ‘montage’ as something that relates more broadly to your practice?

Maxwell: That’s a nice idea, because even when we were talking about the two works we had just done, that opened one day after another in two different countries on either side of the Atlantic. Already, that’s a kind of edit. Like there’s a montage of two totally different scenes, butted one to the other but I think this also describes…

Hadley: The splice, or the space between the cuts like the jump cut. It’s funny because we’ve been thinking about our practice in terms of collage, and especially recently with our interest in cubism. I’m trying to think of what is the difference between montage and collage and maybe it’s that montage is considered a kind of linear collage. It’s time based and I think we still want to include this element of time, but to try to figure out a way to manifest it. Not necessarily in a linear sense or one thing following another, but in a way of overlapping where in the role of editor the viewer senses themselves discerning things and picking things out and pushing things away. We’d like for the kind of volume of impulses or input to be determined by the perceiver rather than ourselves. With 1+1-1 we did think about it as kind of a resistance to the auteur, to the great Godard, seeing what would happen if you dispersed that over a collaboration, but also to include the audience as a kind of collaborative force. I guess that it occurred to me going through our projects, that there is always this desire to set up a kind of ambivalence within the dialectic. We choose two poles and try to charge the magnets of those poles, so that you’re being shifted back and forth between them. I don’t think that’s necessarily a montage format, because you can go back in time, whereas with film, you’re in that scene and you’re propelled forward…

Hadley: Maybe we’re labouring the question too much. There’s a really nice text and I don’t remember who had written it, it was an early film critic, and he made this amazing observation, right from the opening scene of every film; even though we know that the technical apparatus of the camera just opens up on to a scene, that because it’s in a film, absolutely every object in the frame suddenly is pregnant with the coming plot. This changes one’s view of ordinary things. Early on montage was invented to try and make sense of jumps in time and space, but if you take this thought that everything in frame is towards the narrative or the plot, the different cuts lose some of their difference, some of their intense difference, and I think filmmakers know this and are trying to enrich the jumps. At least interesting filmmakers. David Lynch comes to mind as someone who can make a cut in a really strong way and I think Godard also wanted to play with that sense of the destiny of the film to move forward. This is another way of getting to your question around the idea of installation. It’s a thickening of this montage notion. We’re trying to resist it all looking like it’s contained in a particular plot line.

Jenine Marsh: You’ve spoken about an absent figure in some of your works including I and How To Kill A Buddha, and I think that’s a really compelling concept. Is this absence a role for the viewer to fill, or do you think of it as presence in and of itself, a sort of spirit that activates the work? How would you define that absent figure?

Maxwell: I immediately want to say both, but (to Hadley) do you have something you want to add?

Hadley: Well it’s just making me think of this quote by Lisa Robertson and in her most recent series of essays and she says, I’ll have to paraphrase, “absence is the stage for the presentation of presence.” You have to have some way of staging. There has to be something present that makes the stage for absence, to sense something missing. There’s a radical potential in sensing the possibility of you not being here and so you experience your existence. There’s a potential for our personal ontology, which is always in relation to senses, and senses are all relational, so we are here in relation to all these things that are around us.

Maxwell: It’s nice to come back in our practice to a point where we’re really thinking quite simply about figuration again, and to begin to make a figure you have to take a figure away as well, a kind of Gordon Matta-Clark thing. We’re just realizing that we’re coming to that in the works of the last couple years. It’s been closing in on figuration again in a very particular way and now we have three sort-of hypotheses that we’ve collected. One’s an interesting thing from Ian Wallace where he talks about the horizon of painting that is the stage for that absent presence, which makes it possible for that absence to arrive. It’s the monochrome, the monochrome is the horizon for painting and we came to our Improperties installations with these cut sculptures. We cut them up in such a way that we could align them on a plane extended, so that the plane could be the horizon of sculpture. And really recently we had this epiphany that 1+1-1 plays with the space of the synesthetic, every sense firing off at the same time. All sensation arriving at the subject all at once, and this would be the horizon for installation art. So it’s an interesting series of epiphanies along the way that we’ve kind of constructed

Hadley: What’s the third one?

Maxwell: That’s the third one. So, one is the monochrome, two is the plane…

Hadley: Oh I see, painting, sculpture and installation…

Maxwell: Yeah.

Hadley: I get it. So the first one is Ian’s and then we get to have the other two! But you know what else I realized, I was just weirdly reading a couple pages from our Master’s thesis yesterday and there is this element of it where we talk about us figuring ourselves in relief, in relief of the other, and I realize that’s what we’re doing with this black foil now. It’s literally a relief of a figure, of a stone figure, but to transfer that kind of thinking of how we understand ourselves in relationship to working collaboratively…

Maxwell: We realized when we were writing our Masters that through working together we’ve always, I guess we’ve been able to be together for so long, because we don’t assume to know each other. We don’t think you can know each other really directly. We can know each other through interactions and traces and the process of our making is a really good example of it where one of us might put something forward, the other will make some kind of alteration and its in the alteration, seeing what you’re doing, and knowing what you’re thinking behind the object and seeing it altered that you get a sense of how the other person is thinking. In a way we’re returning to this absence presence that you had asked about, defiguring something to refigure it. I have a sense of Hadley when she alters something that I’ve done and then of course we have the new changed figure. I make a change and she makes a change, and so we keep sensing each other in these alterations. We call it pressings against a… What’s the durometer of sense? We have these really weird terms for it, but my god your right…

Hadley: Touch, violent encounter. All these terms that are about collision and pressing and durometer…

Maxwell: The foil is exactly doing that, gosh that’s bizarre.

Hadley: Yeah we should have thought of it along time ago! We’re really slow.

Maxwell: Yeah, how many years ago was that? 8? There you go, 8 years ago. Don’t sweat if you’re making sense from work to work, just go for it, go to where your wonder is and you’ll find that these things come back. That’s taking wonder in your own working instead of always trying to be so deliberate, precise. Just jump in with wonder and stuff will come back. It’s very weird!

Jenine Marsh: You’ve described your work in cinematic terms, the montage, the cutting and yet it functions quite theatrically. In relationship to ‘crowd’ the theatre and the cinema operate very differently, they have different kinds of crowds, different kinds of participation. Could you elaborate on your works relationship to these two terms ‘the theatrical’ and ‘the cinematic’ specifically in relation to ‘the crowd?’

Maxwell: Again our interest in working in different forms is to be effected differently. The practice is such a way so that it adapts, but I’ll say that we would resist that there’s one paradigm that it works in. There’s a kind of curiosity for experiencing each medium differently, not trying to make them too similar. However, it’s fun to borrow from another discipline. We tried to make a photograph really sculptural for instance and that’s part of the reason to interrogate each medium intimately, so that when you cross them you really know what the alchemy is that’s happening. The cinematic is one that we feel like we borrow from to try to alter it, because its been the dominant one through the twentieth century. It’s a reified medium in a way and we want to profane it, to haul it down, which means to use some of its conventions in a different way. I also fall asleep in films now. I didn’t use to, I use to find them super intriguing, but just sitting there, in the chair and just gently rotting for two hours is just not enough for me anymore. I like to move and I like to be in a different relation and in a different time zone with it too. This is what Roland Barthes was anxious about with film. He said he couldn’t have his own time with the artwork and I sense that now. So the theatre offers a kind of relief from that tyranny of the time that film takes and the positioning that film makes you sit in as a viewer. It has a monumental quality that way because you’re sort of ignored as a particular person, the way that a giant public sculpture ignores you walking by…

Hadley: Except that you understand that you’re supposed to sit in a certain place and look in a particular direction. I mean theatre is constantly playing with that, but they have to have those conventions to play with and with installation the conventions are very few, so if we can take the conventions of film or cinema and theatre and then undo them it gives us something to work against. So to say we’ll make a physical montage of cinema that you can walk through and pace yourself, or a theatre that happens simultaneously and is ordered by your movement through the space, it actually gives us something to resist in an installation space. That’s kind of why we use it. It goes back to your earlier question of when you’re in Berlin what do you do when you can do anything? You choose things to resist, or we did so that we could continue to work. We also use it for the pleasure of undoing its conventions. It allows us to stay in the conventions of a gallery exhibition, because we do still believe in contemplation, and contemplative space, and I feel slightly apologetic about that. That’s why we choose other things to resist, so that we can protect contemplative space. That’s probably why Nuit Blanche was so traumatic for us, because that does not exist. It’s a very good thing to have us confront that and see what we can do in that situation.

Aryen Hoekstra: To follow this thread of resistance a bit further, in projects like 1+1-1 and Silly Love Songs your source material has had a very direct connection to movements of resistance and you’ve spoken about freeing these from their current reified position. Could you speak about the relationship to resistance within your own practice and your conception of the role of resistance within a broader art context, or if you prefer, the role of art in relation to a broader conception of resistance?

Maxwell: Which can be like resisting your own self-promotion, or letting the noise buzz, giving it the moment to make a buzz and hold yourself back for a moment and be receptive. I think you’re right, we’ve talked around a lot of these things and if I was to throw out a larger problematic that we see our practice in general trying to negotiate, its this one of resisting formalizing, or ritualizing, or institutionalizing human behaviours. Looking for an art that resists that alone, and that’s a lot, that’s really a lot for a practice to do and for an artist to do. And it takes very odd, subtle forms, because if you set out to work in a way that resists formalization, I mean the absolute formalization, not formalism, but really totally programming our behaviours, some things can look like they’re formalized but the person behind it isn’t. We were describing Noh theatre, with an actor and a mask. You might think that person is tyrannized in this production, but they’re actually experiencing themselves, an incredible living struggle and wonderful freedom in having the space to do that. In a way, it means that appearances are always not what they seem. We need to really chase down these things and make sure that we aren’t making one to one connections. Well it looks like this, so it must be this. No, we need to keep opening them up, activating things that seem to be becoming rigid, becoming formalized. And formalized is immediately always ritualized, its always one and the same thing. That’s why the word profanation came up for us. The other critical terms, for instance ‘normativity’, its not strong enough, because we’re concentrating power, and when we’re concentrating power we’re elevating something. This is where all these divine aspects going back to the foundations of art, the Western-European-Christian paradigm, this is where it all really begins. So profaning is better than even critique. Critique isn’t enough, its too weak! It makes a cut and runs for cover and hides and then waits for someone to do something productive and then makes a cut and runs away and hides. Critics know this. They know they have to offer something more, they can’t just cut, they have to offer, conjure a form, conjure a working…

Hadley: We’ve been reading Kant again in the last couple of days and it seems to be that he’s saying that the capacity to critique is actually the most human of traits. It reminds you that there’s this whole tradition that says the judgement of poetry is worth more than poetry. Part of our interest in these resistance movements, but more so the aesthetic remnants of these resistance movements, is that we sense that there is something else about wanting to belong to that movement. Wanting to identify yourself with that ‘we’, or that crowd, that particular crowd that says something about our humanity and our desire to be with one another and our desire to sense ourselves in relief, in resistance. In resistance and relief you need the pressing and there needs to be a kind of violence to the encounter to be able to sense yourself in relief to others. Silly Love Songs was very much for us about the love that is part of that desire to express yourself with other people. That whole movement was driven by some kind of force that belongs to love, and not just necessarily anger or boredom…

Maxwell: The great twentieth century product par excellence.

Hadley: And that keeps coming up in all the movements we’ve been looking at too. Boredom is a great part of it, but love also returns to it, is always part of that. So, resistance and what is love’s role in that?… I don’t know if that was actually an answer to the question, but, your question made me think of that. It’s an important element, and we don’t say it very often. We don’t say the word love, like it’s just not…cool. Not yet…

All images appear courtesy the artists.